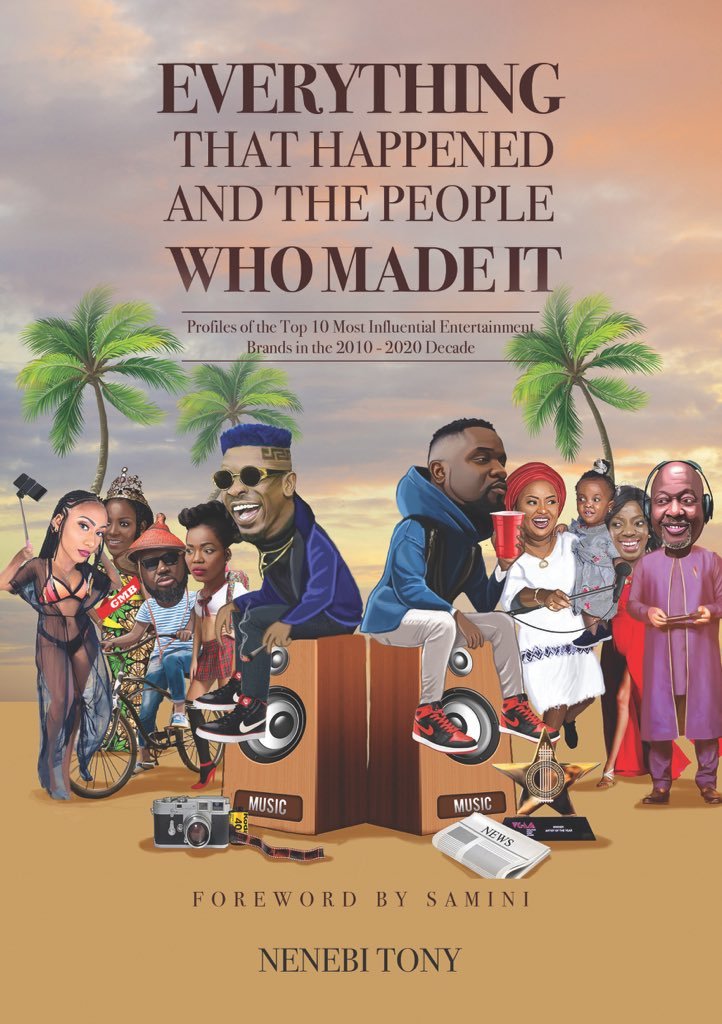

Review of Nenebi Tony’s Book ‘’Everything That Happened And The People Who Made It”.

Documenting a decade of interesting, yet important cultural shaping events within the Ghanaian entertainment landscape is an arduous task especially for a writer considering the paucity of information available – due to lack of proper, and verifiable documents.

Under such circumstances, one is inclined to rely on memory, reliable bits and pieces of information, and direct interviews with stakeholders and observers of the art space. That’s exactly what writer, and researcher Nenebi Tony did in his book “Everything That Happened And The People Who Made It”.

Across 194 pages, Nenebi Tony recounted interesting moments and incidents, confirmed by the people directly involved. As a young journalist covering arts and entertainment, he happened to have witnessed some of these moments giving him first hand accounts of these incidents. Nenebi Tony also drew expert thoughts on some issues and topics to get a better understanding of some of these significant moments.

Novel-styled narration mixed with direct interviews and academic research presentations is the style of writing he adopted in this book; a style that did not diminish the fervour that made it interesting and readable. Though a lot of pages (if you are not an avid reader), “Everything That Happened And The People Who Made It” is a book that you would not like to stop reading as each page or topic segues into another without ruining the plot or experience.

Clarity on issues that have informed the art scene was thoroughly discussed in this book. For example, under “Music Is Universal; Language Is Not” (Page 23-44), Nenebi Tony examined the musical history of Ghana and Nigeria, capturing the history of the relationship through two music powerhouses- Goodies Music and Kenny’s Music. The two labels leveraged each other’s influence in Ghana and Nigeria respectively to permeate the markets. However, what was insightful is the role that Tic (formerly Tic Tac) played in kick starting the whole Goodies Music- Kenny’s Music relationship.

Despite his role in forging that business relationship and by extension, the Ghana- Nigeria musical bromance, Tic felt betrayed by Goodies Music CEO when he favoured the legendary music group V.I.P over him, a move that informed his decision to leave Goodies Music.

Another artist, MzBel, signed to Goodies Music during her career also gave Goodies CEO his flowers for helping her career. She, however, felt abandoned by Goodies at the lowest point in her career when armed men attacked and sexually abused her. To her, Goodies’ unavailability during her trying time was unpardonable, a sentiment Goodies conceded.

One of the highlights of the book was recounting the history of the Ghana Music Awards.

The prestigious music event’s 20-year run is not a fluke – the founder, Iyiola Ayoade’s resilience, vision, and quest to help develop the space seemed ingrained in Charter House and the personnel running it. Nenebi Tony details how Iyiola sold his vision to Ghana Television (GTV), to have the first edition of the Ghana Music Awards telecasted live, the uncertainties,the team that was assembled, and finally, how the event became a success in 1999. Nenebi’s ability to interview some of the people involved in making the debut Ghana Music Awards a success like Nanabenyin Dadson, Paa John Dadson, and Moses Gyapong of GTV while capturing the hoops that they scaled was eye-opening.

Chapters were dedicated to Sarkodie’s emergence, dominance, and business acumen over the years, with emphasis on the “I’m a business-man” trope made famous by Jay-Z. Nenebi Tony spent time tracing the circumstances that led to Sarkodie headlining and subsequently owning Rapperholic – his annual event entering its 10th year into a staple on the Ghanaian event calendar.

If Sarkodie represents a carefully built brand to appeal to a section of the populace, Shatta Wale is an example of how to cut across demographic stratas. His rise, his almost cult-like following is an anomaly in terms of attracting corporate sponsorship. What makes Shatta Wale thick? Why does he appeal to a wider demographic including the ‘elite’ despite his “street” image? And, how come he gets away with a lot of career-ending ills? This nexus between the two musical behemoths and the questions posed are explored in this book.

The rise of hiplife in 1994 and its subsequent evolution – the emergence of sub-genres and the activities of some artists were treated. Accra has always been the epicentre or the point of diffusion. However, Tema played a significant role in pushing the genre to a recognized point. While Nenebi spent a considerable moment exploring the contribution of the Tema-based artist and the emergence of “Twi Pop”, it was disappointing to see no mention of the Skillions, a pioneering group, and their role in making “GH Rap” a thing, thus inspiring a whole movement of English rappers. Again, Kumasi, a significant region in the history of hiplife didn’t get a mention and thus treated as a footnote in the whole discourse.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, there was a “Radio & TV” Magazine in circulation. The magazine captured all the happenings within the media space. One of the articles that stuck with me focused on how far-reaching the radio frequencies of major Accra-based radio stations spanned between Accra to Cape Coast. At the end of the article, Joy FM and Peace FM were the two stations with “powerful” bandwidth. That said, these two radio stations have been at “war” with one another. Joy FM was the leading station for a long while, satisfying a listenership considered “elite and educated”. This meant; a section of the non-educated was out there for the taking.

That untapped market was what serial entrepreneur Kwame Despite saw, leading him to establish Peace FM, the first Twi-speaking radio station in Ghana. Not only did the station satisfy the “uneducated” and Twi-speaking listeners, but he was also able to bring on a host of presenters with the requisite skills to capture these audiences and more. The success of Peace FM led to a change in the media landscape in terms of the use of local language as a medium of communication. Sensing how successful Peace FM was becoming, Kwesi Twum, owner of Joy FM acquired the English-focused Groove FM and turned it into Adom FM, which employed Twi as a medium of exchange.

What Nenebi does is to pan out the history of private radio broadcasting in Ghana – starting with Radio Eye, established by Dr. Wireko- Brobbey, which was subsequently shut down by the J.J. Rawling administration despite the 1992 Republican Constitution bestowing on Ghanaians the “freedom of speech”. That constitutional clause was tested by Dr. Wereko-Brobbey in the Supreme Court in 1993. His motion was upheld by the court resulting in the establishment of private media houses including Joy FM and Radio Gold in 1995.

In the film sector, he gave Shirley Frimpong-Manso her flowers for singularly helping change the face of movie making and premiering in Ghana. (You should read the book to appreciate her vision and works). There are chapters dedicated to the irrepressible Nana Ama McBrown and her transmogrification from a radio presenter to an actress, tv host, and brand ambassador for many companies. Her evolution and career have been incredible.

Although Nenebi spent time highlighting the contributions of some top journalists in the entertainment scene such as Nanbenyin Dadson and the role TV3 has played within the media space with respect to his archy programme “Ghana’s Most Beautiful”, I would have loved to read the contributions of people like Ameyaw Debrah on his role in popularising celebrity news reporting through new media and the works of Abraham Ohene-Djan (music videos)/ or Ramesh Jai Gulabrai of Apex Advertising.

As much as celebrity culture and new media (blogging/vloging) have become a thing, not much has been written about his contributions to the new media ecosystem. (Respect to you Mr. Ameyaw Debrah).

The same could be said of Ohene-Djan and Ramesh Jai, who have played a significant role in the audio-visual space – helping nurture a generation of music video directors and advertising creatives. (I get that this book discusses happenings within a decade but it must be said that the likes of Ramesh and Abraham Ohene-Djan are still putting in the work. Plus, what they did decades ago are still of great significance).

“Everything That Happened And The People Who Made It” is an important piece of work. Nenebi Tony wrote a book that serves both as a historical and educational material. Where research was inadequate, Nenebi employed interviews to augment the narrative, giving the reader primary information on what is being discussed. In an arena where information is very unreliable, research materials non-existent or partially existing, Nenebi’s book comes to fill a gap for all entertainment writers in Ghana and elsewhere as well as followers of the scene.